The Gimmick Shows

Brain power to blondes

Brain power to blondes

A cheap novel, a cheap author, but a true if trite statement on page thirty-seven: ‘You got talent, you got looks but you ain’t got a gimmick … and without a gimmick you’re lost, son … go home, find yourself a gimmick.’

There are two types of success stories: the long hard grind – and overnight fame. Occasionally one follows the other. More often the gimmick leads to the second in, if we may quote the same novel, ‘a great big hurry’. Successful TV gimmick shows are the give-away programmes, audience participation games, the panel games with that extra ‘something’ which makes them click.

What is a gimmick? Johnnie Ray’s cry is a gimmick; Winifred Atwell’s other piano is a gimmick, and well – now you know what we mean. In the case of the quiz show one is led to believe that the word is an abbreviation of ‘gimme’ or ‘gimme quick’.

Having accepted the premise that a gimmick is something worth having, let us examine a few of the gimmick shows.

Pride of place must go to the fabulous The 64,000 Question, ATV first showed this programme on May 19th, 1956. The whole show was based on a lowest common multiple of sixpence. Now, a sign either of inflation or of the increasing prosperity of Independent Television the show works in multiples of a shilling. Answer eleven very hard questions accurately and you can leave the studio, after five appearances, with £3,200 in your pocket – or, if you accept the Val Parnell bonus and take the whole amount in Defence Bonds, £3,520 – and a halo of national fame gleaming over your head.

The English show is based on the world-famous American The $64,000 Question. The main differences between the two programmes are that Hal March comperes the American version and Jerry Desmonde the English one; the English show is transmitted on Saturday night and the American on Tuesday evening; and whereas our 64,000 shillings aren’t taxable, their 64,000 dollars are! In the United States they have police to guard the safe containing the money. In this country ex-Superintendent Fabian of the Yard performs the same function, and is one of the many precautions which are taken to preserve the integrity of the show.

All sorts of people can achieve fame overnight through this competition. In America, a woman doctor of psychology won 64,000 dollars by answering questions on boxing, a railway porter won a huge prize for his knowledge of astronomy, and a parson impressed the nation with his expert knowledge of – jazz! A twelve-year-old school girl (she won umpteen thousand dollars spelling ‘Antidisestablishmentarianism’), a marine captain (on cooking), a coalminer (on the Bible) – all have been big winners.

Such people are the life-blood of the show. Questions are far from easy, stakes are high and contestants cannot answer questions on a subject from which they earn their living. The publicity around the show is enormous and needless to say the winners have many lucrative offers. Viewing figures are vast – in America the sponsors can really boast that the programme stops the country’s activity for the half hour that it is on.

In the near future it is hoped that there will be a challenge competition between the winners in America and the winners in this country. A battle of giants, indeed.

A great deal of the popularity of the show can be traced to its simplicity. From the first to last questions the cash prize doubles itself. Thus in England the first question is for 64/-, the second for 128/- and so on to 64,000/-.

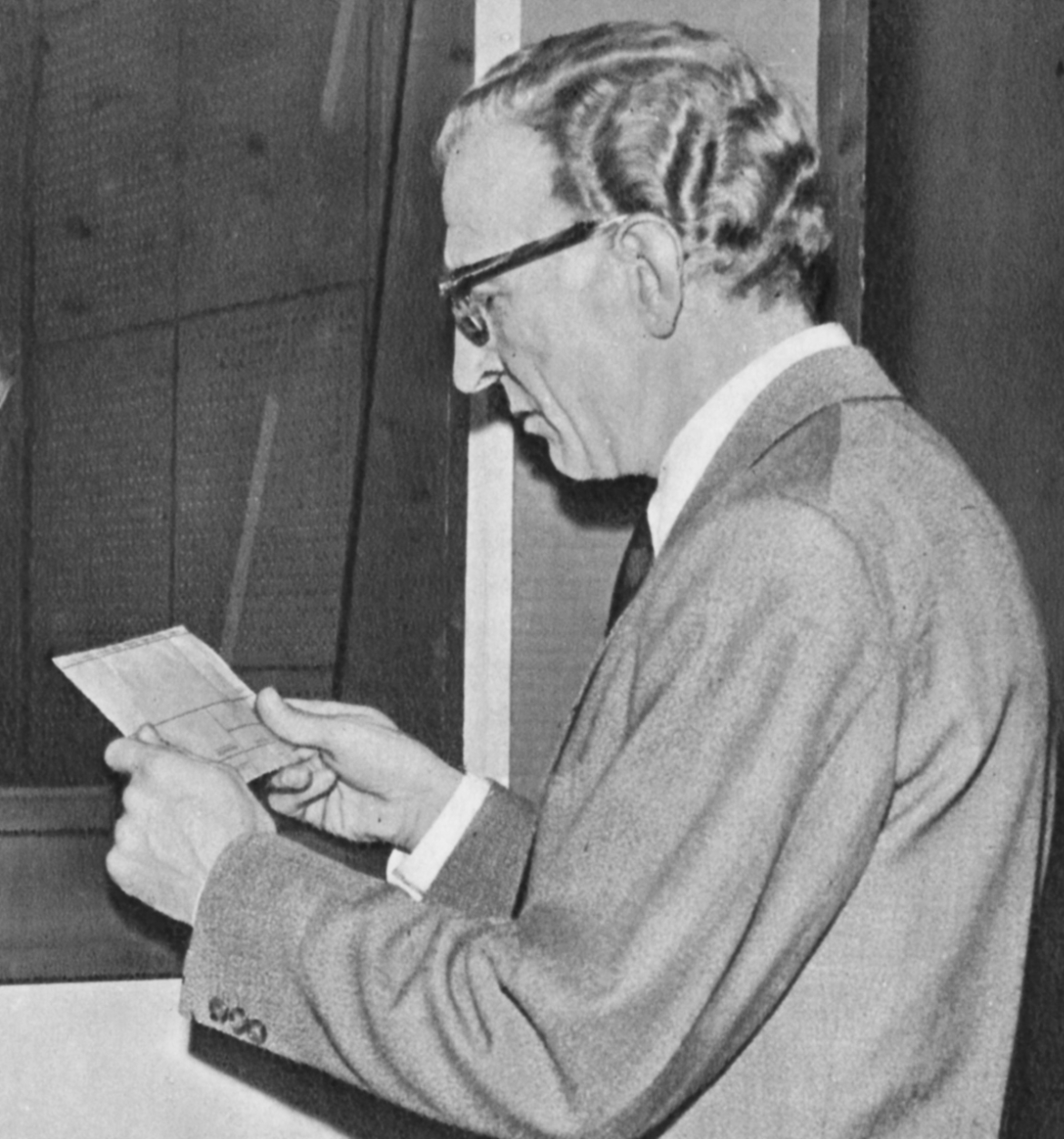

The first major excitement of the British version came when Vernon Goslin, a forty-two year old schoolmaster, answered six of the seven parts of the 64,000 question, only to fail at the last part. There have been a great many excitements since then. For example, there was the day when Ashley Neville Stacey, a schoolmaster from Bexley Heath, reached 64,000, with his wife and five children there to watch him, only to find the last Biblical question too difficult for him. A couple of weeks later, Albert Norman, a 65 year-old retired diamond setter from Normany, Surrey, became the first person to overcome the final hurdle and walk away from the studio with £1,760 worth of Defence Bonds in his pocket.

Shortly after this there was great excitement when the top prize was doubled and contestants began trying for £3,200.

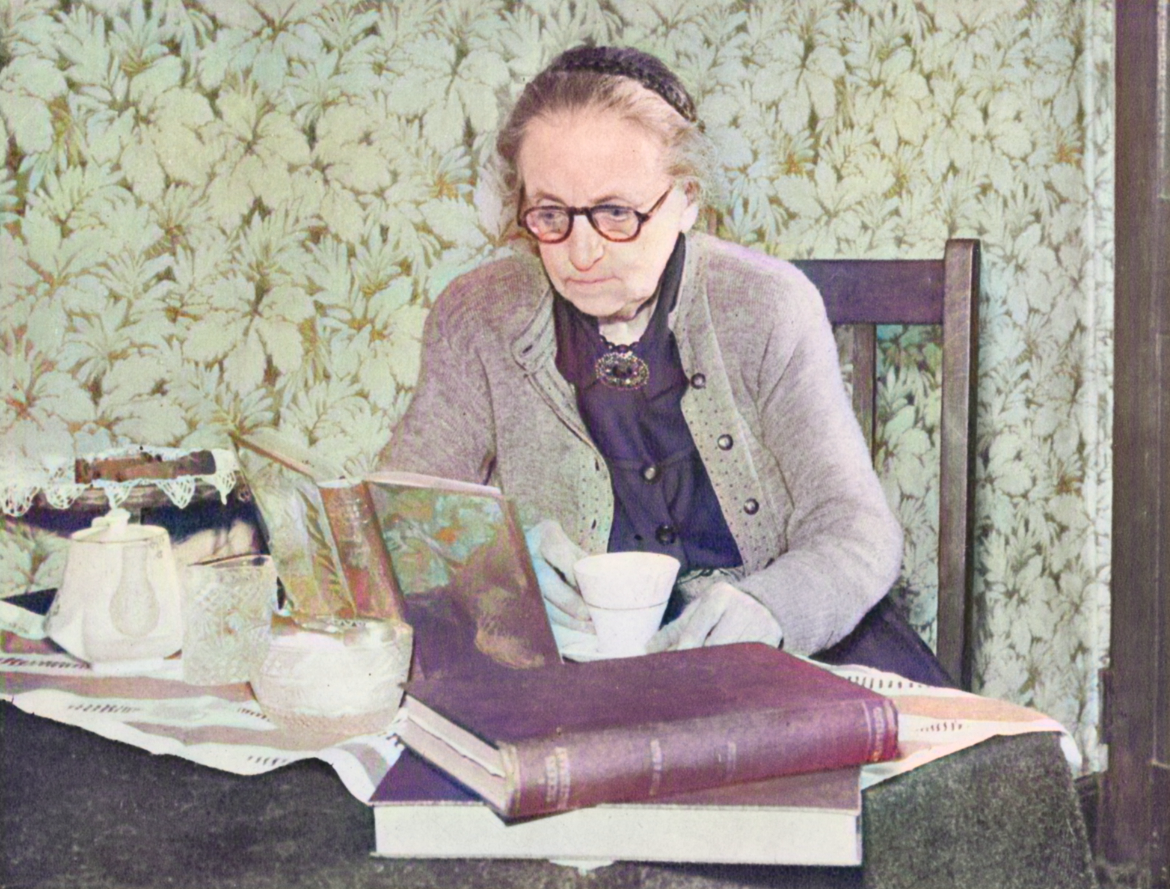

On Saturday, 13th October, 73 year-old Miss Jane Brown staked her reputation as a Dickens scholar on winning the big prize. She won all right, and with £3,520 in Defence Bonds this gentle old Victorian lady went home to Wolverhampton, her black cat, and her organ which she bought in a jumble sale. Self-taught in shorthand, Miss Brown has thirty pupils who were, no doubt, among the millions who sighed with relief when the final question was answered.

Many of the contestants in this country become singularly attached to the show, and it is not unusual to see half a dozen or more ex-competitors appear on the screen when producer John Irwin turns the cameras to spotlight audience reaction.

Another exciting money game is Beat the Clock, which features regularly in Sunday Night at the London Palladium. It is compered by the breezy comedian, Tommy Trinder, and relies for its impact on the participants being willing to undertake some pretty gruelling ordeals. Bursting balloons by sitting on them (blindfold, to make matters more difficult) is one of them. Another involves running six laps of the stage, eating a roll at the end of the first lap, drinking a glass of milk at the end of the second, playing hoopla at the end of the third, bursting a balloon with a dart, riding a hobby-horse and so on – all six laps to be completed within a minute.

Viewers have been amazed at the variety and ingenuity of the actual problems posed in this game. They find themselves asking what kind of diabolical mind would think of asking contestants wearing divers’ boots to burst balloons by jumping on them; what kind of sadist would expect his victims to stack cups of tea with their hands encased in boxing gloves. The answer to these questions is producer David Main, who selects the ordeals from among those used for the same game in the United States.

At any time during the fourteen minutes’ duration of Beat the Clock a bell may ring – the bell which means it’s jackpot time! All contestants immediately stop their efforts to win television sets, refrigerators, washing machines and motor cycles and concentrate on winning some hard cash with an even more difficult problem than dancing on balloons with leaden boots. The jackpot question often involves real skill; bouncing four balls into four boxes placed one above the other on a pole, for example. The jackpot has been won at varying values. On two of the first three occasions the prizes of £1,100 and £1,300 were the highest ever to have been awarded on British television. The lucky winners? A honeymoon couple and a sailor on leave with his wife.

Hit the Limit is a show which began life from Midlands transmitters only, but because of its popularity was soon being relayed from London as well. Announcer Peter Cockburn got his lucky break in this programme when its M.C. Jerry Desmonde, vacated the star-role to make a film with Norman Wisdom.

Hit the Limit is not really an intelligence test, for the questions are simple and the whole atmosphere is that of a brisk fairground. The basic idea is that competitors throw a dart at a revolving wheel which contains a V-shaped ‘jackpot section’ – total area 95 square inches, or one-twelfth of the board. According to which section the dart sticks in, questions are asked and cash prizes awarded. The value of the jackpot increases by £50 each week.

If ever a show had a gimmick it is the highly controversial Yakity Yak – The Dizzy Show. Why controversial? You should just see the mail that pours into ATV. It would appear that half the viewers want to send the girls who participate to the Siberian salt mines, and the rest would like to see them enthroned on pedestals of gold for having achieved the ultimate in feminine pulchritude.

This programme was based on an observation which Michael Pertwee made almost every time he met a woman. ‘They never admit they are ignorant of any particular fact,’ he told Leslie Goldberg, the executive producer, one day. Out of these ten little words came one of the most genuinely funny shows seen on television.

The recipe was simple enough. Choose four beautiful girls, put them on a panel, add one MacDonald Hobley if the programme is to be seen in London, or one Michael Pertwee if it is broadcast to the Midlands. Select ten or so words which sound as though they might mean something they don’t and ask the girls to explain them. The girls must give an answer, and it must never be, ‘I don’t know’.

The result has sent shivers up and down the spines of the erudite gentlemen who compile the Oxford English Dictionary; has made viewers incredulous that even a very dumb blonde could think a toupee was an abbreviated two-piece, or a Bombay Duck a duck with an extra long leg; and has caused a great many people the heartiest of belly laughs. And of course it has given the Press the chance to publish even more pictures of girls with trim figures and cute faces.

John Irwin who produces the show added another gimmick. At the end of each programme the girls were asked to discuss a debatable topic. This resulted in brain machinery working overtime. The girls produced such classic remarks as: ‘Men are so stupid – whenever I want to read what’s going on in Cyprus they are reading the sports page. That’s why I hate travelling in Undergrounds…”

A last word on the gimmick. If you can think of one which ATV could use, send it to them, they’re always looking out for fresh ideas.

About the author

The ATV Show Book (later editions were not sponsored by ATV) was an annual produced in the late 1950s and early 1960s